Photo by Daniel Shirey/MLB Photos via Getty Images

Restrictions on the shift and other tweaks coming to MLB this season

That sound you hear, off in the distance?

That is the sound of spring.

Baseball is just around the corner, as pitchers and catchers participating in the World Baseball Classic reported to training camps on Monday, February 13. Position players participating in the WBC are slated to report on February 16.

With a new season around the corner, MLB is implementing some new rules for the upcoming year that might make baseball look — and feel — different than it has the past few seasons. Here are the rule changes for 2023, explained.

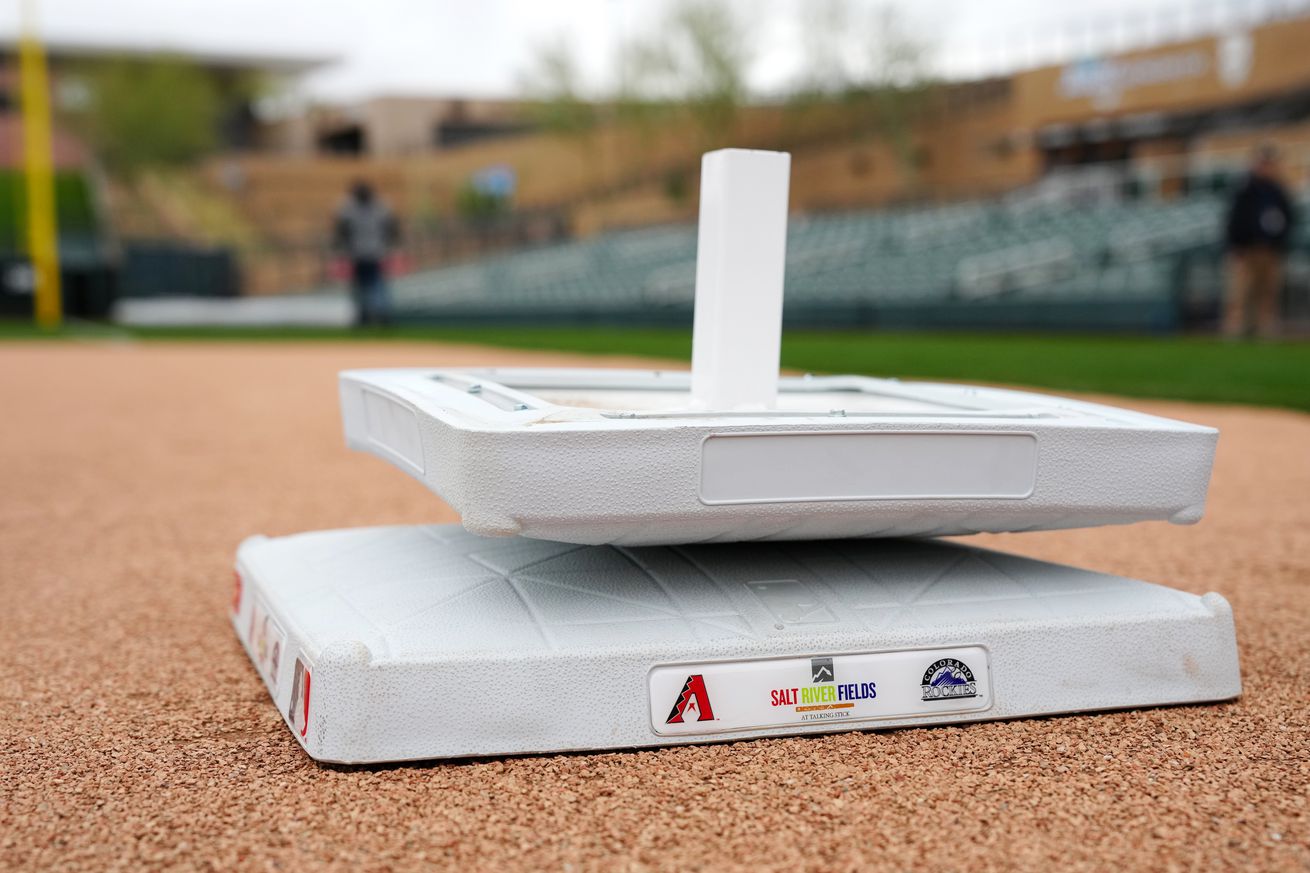

Bigger bases

Photo by Daniel Shirey/MLB Photos via Getty Images

This might be the most visible rule change, at least at first blush, and the easiest to explain.

Bases this season are now bigger, increased in size from 15 inches on each side, to 18 inches on each side.

There are a few reasons for this change. First is safety, as the bigger bases gives both a player in the field, as well as a baserunner, more room to operate. This may cut down on collisions at first base, for example. With the implementation of larger bases in the minor leagues, “base-related” injuries dropped by 13.5% overall, and there were declines in “base-related” injuries at every level.

There is also the idea that base runners will be more aggressive, in particular when considering stealing. With the distance between bases now reduced by 4.5 inches, base runners are that much closer to their next destination. However, results have been mixed. According to one study, the success rate on stolen base attempts increased between one to two percent. However, in the International League, the success rate on stolen base attempts dropped from 76% to 75% with the implementation of larger bases.

Also, if you are wondering whether the larger bases impacted the general baseball rule of 90 feet between bases, that is measured from home plate to the back corner of both first and third base, and from the corner bases to the middle of second base. That is unchanged with the larger bases.

The pitch timer

One of the major complaints about baseball over the past few years has been the length of games. MLB games lasted an average of 3:04:24 last season, which was actually down by almost ten minutes from 2021, as games lasted an average of 3:10:04 during the 2021 season.

In an effort to speed up the pace of games, a pitch timer will be implemented this season.

When the bases are empty, the pitcher has 15 seconds to begin their delivery to home plate. When there are runners on, the pitcher has 20 seconds to begin their delivery.

The batter, for their part, must be in the batter’s box and “alert” by the eight-second mark on the timer.

If the pitcher does not start their motion prior to the timer running out, they will be charged a ball. If the batter is not ready and “alert” by the eight-second mark, they will be charged a strike.

The pitcher is also allowed two “disengagements” — either a step-off from the pitching plate or a pick-off attempt — per plate appearance without penalty. A third such disengagement will be an automatic balk, unless an out is recorded. In other words, if a pick-off attempt is made as part of a third disengagement, and the runner is thrown out, there is no penalty.

This all probably needs a bit more explanation, so we can dive into it a bit more.

The rule requires a bit of uniformity, with respect to when a pitcher has begun their delivery. As such, MLB is going to be more strict with how a pitcher begins their throwing motion. When using the windup, a pitcher is allowed one step back, and one step forward. When throwing from the stretch, a pitcher may tap their front foot, but they must come to a complete stop, and the pitch timer stops when the front foot is lifted again.

What does that mean? For one thing, the end of Luis Garcia’s “rock the baby” windup:

Luis Garcia’s windup is now considered illegal with MLB’s new balk rules pic.twitter.com/rtDuSPFNOj

— The Game Day MLB (@TheGameDayMLB) February 15, 2023

Throwing motions not in compliance with the above will result in a balk, so we might see more balks this season.

For hitters, they have to be in the batting box and “alert” with eight seconds remaining on the timer. This means they have to be looking ahead at the pitcher, with both feet in the box. They do not have to be in a batting stance, but have to be in position to get into their stance quickly.

This likely means we will never see a pre-pitch routine like Nomar Garciaparra’s ever again:

Nomar’s batting routine. Every ball player growing up from ‘96-‘06 tried this at least once. pic.twitter.com/fp4Ml3xu59

— OBVIOUS SHIRTS® (@obvious_shirts) October 17, 2020

Batters are also allowed one time out per at bat.

Now, how will all of this be enforced? There will be pitch clocks in center field and behind home plate, similar to the play clock at an NFL stadium. There will be two in center field so that the home plate umpire can see at least one of them, whether there is a left-handed batter at the plate, or a right-handed batter. There will also be two behind home plate, so that the pitcher can see one regardless of whether there is a left-handed hitter or a right-handed hitter.

The umpires will also be equipped with a belt (the home-plate umpire) or a watch that buzzes when the timer expires.

Given all these adjustments, will the pitch timer be worth it? Consider this. In Triple-A games last season, the pitch timer contributed to a reduction of just fewer than 21 minutes per game compared to 2021.

Pickoff limitations

Photo by Tim Nwachukwu/Getty Images

As noted above, pitchers are now allowed just two “disengagements” per plate appearance without penalty. Stepping off the pitching plate counts as a disengagement, as does a pick-off attempt. If a pitcher makes a third disengagement, and an out is not recorded on the bases, the pitcher will be charged with a balk.

If, however, the third disengagement does result in an out on the bases, there is no penalty.

If a baserunner (or baserunners) advances during the course of a plate appearance, then the disengagement counter resets.

For example, say there is a runner on first base. The pitcher tries one pick-off attempt, and then steps off the pitching plate. That counts for two disengagements. Then the pitcher delivers to home plate, and the runner on first steals second base successfully.

Now the disengagement counter resets. The pitch timer rules as just discussed, however, remain in effect the entire time.

The reason for this tweak? MLB wants to see more action on the basepaths. Stolen bases are exciting, after all. Since using this rule in the Minors, “steal attempts per game have increased from 2.23 in 2019, at a 68% success rate, to 2.83 in 2022, at a 77% success rate.”

Restrictions on the shift

The other major rule change?

Say goodbye to the extreme defensive shifts we have seen in recent years.

Now, at the time a pitch is throws, there must be two infielders on each side of second base, on the infield dirt or the infield grass. Infielders can move after the ball leaves the pitcher’s hand — more on that in a moment — and the penalty for a violation is an automatic ball.

In considering this rule, MLB consulted with teams, managers, and coaches on possible ways of circumventing the purpose and spirit of the rule. As such, teams cannot put a player “in motion” to try and defeat the rule. So, if a left-handed batter is up, do not expect to see the shortstop start to sprint towards right field, timing their run to coincide with the pitch coming to home plate. That will be treated as a violation.

Also, position changes are now limited during the course of an inning. If you are the shortstop at the start of the inning, you have to remain at shortstop for the duration of the inning, unless there is a substitution or an injury. This prevents teams from putting their best defensive players at a position based on the hitting tendencies of each batter during the inning.

Now for a few points of clarification. “each side of second base” is determined by the corners of second base, not an imaginary line running from home plate through the middle of second base. It might not seem like much, but we do have bigger bases this year, remember.

Also, the infielders are required to be on “each side of second base,” and either on the infield dirt, or the infield grass. This means that MLB will be paying attention to the size of the infield dirt at each stadium. According to MLB, “the outfield boundary is defined in the rule book as a 95-foot radius drawn from the center of the pitcher’s rubber, and each infielder must have their feet entirely within the boundary (meaning on the dirt).”

Teams that were previously not in compliance with this rule were notified during the offseason, and MLB will be monitoring this requirement throughout the season.

Finally, this is an infraction that the batting team can choose to decline. If, for example, the team in the field is in violation, but the pitch is still delivered to home plate and the batter hits a home run, the batting team can decline the automatic ball … and live with the result of the play.

In this case, a home run.

Ghost runner is back

Must See

-

American Football

/ 12 hours agoThis Big Ten women’s basketball team is an early winner of transfer portal season

Photo by Jason Clark/NCAA Photos via Getty Images With the addition of Oluchi Okananwa...

By admin -

American Football

/ 12 hours agoRBC Heritage leaderboard stacked through second round of play, Justin Thomas leads

Photo by Jared C. Tilton/Getty Images Justin Thomas has the lead through Friday at...

By admin -

American Football

/ 14 hours agoLando Norris ‘confident’ but not ‘comfortable’ after FP2 at Saudi Arabian Grand Prix

Photo by Kym Illman/Getty Images McLaren driver Lando Norris topped the timing sheets in...

By admin